Table Of Content

If you're looking for a more stable investment—especially in uncertain markets—government bonds might be worth considering. They’re often seen as safer than stocks, with reliable interest payments and full repayment at maturity.

In this guide, we’ll break down what government bonds are, how they make money, and when they might make sense for investors like you.

What Is a Government Bond?

A government bond is a debt security issued by a national government to raise money for public spending. When you buy one, you're essentially lending money to the government.

In return, the government promises to pay you interest (called a “coupon”) on a regular schedule—usually every six months—and to return your full investment (the “face value”) when the bond matures.

For example, if you buy a $1,000 U.S. Treasury bond with a 10-year term and a 3% annual interest rate, you’ll receive $30 in interest every year and your $1,000 back at the end of 10 years.

Government bonds are commonly used to fund infrastructure, defense, and other national programs.

They're typically considered low-risk investments because the full faith and credit of the issuing government backs them.

How Government Bonds Generate Returns For Investors?

When you invest in a government bond, you’re entering a long-term agreement: you lend money, and the government pays you back over time with interest. Here’s how that return is structured:

Fixed Interest Payments: Most bonds pay a set interest rate (coupon) every six months. For instance, a 5-year bond with a 4% annual coupon pays $20 twice a year on a $1,000 investment.

Principal Repayment: At the bond’s maturity, you get your original investment back, assuming the government doesn’t default (which is rare in stable countries like the U.S.).

Possible Capital Gains: If interest rates drop after you buy a bond, its market value may rise. You could sell it for more than you paid.

-

Example Scenario:

Suppose you bought a 10-year Treasury bond for $1,000 with a 3% coupon. You’d earn $30 per year in interest.

But say after two years, interest rates fall and similar new bonds only pay 2%. Your bond becomes more valuable (investors expect lower returns), and you could sell it on the secondary market for a profit—say, $1,050.

Government bonds are often used in portfolios to generate steady income or as a hedge during volatile stock market conditions.

Some investors even ladder bonds with different maturities to balance risk and income flow over time.

Types of Government Bonds

Government bonds come in several forms, each serving a different purpose and investor profile.

In the U.S., they’re typically issued by the Treasury Department, but state and local governments can issue their own versions too.

Type of Bond | Maturity | Interest Payments | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

Treasury Bills (T-Bills) | 4 weeks to 1 year | None (sold at a discount) | Short-term parking of cash with low risk |

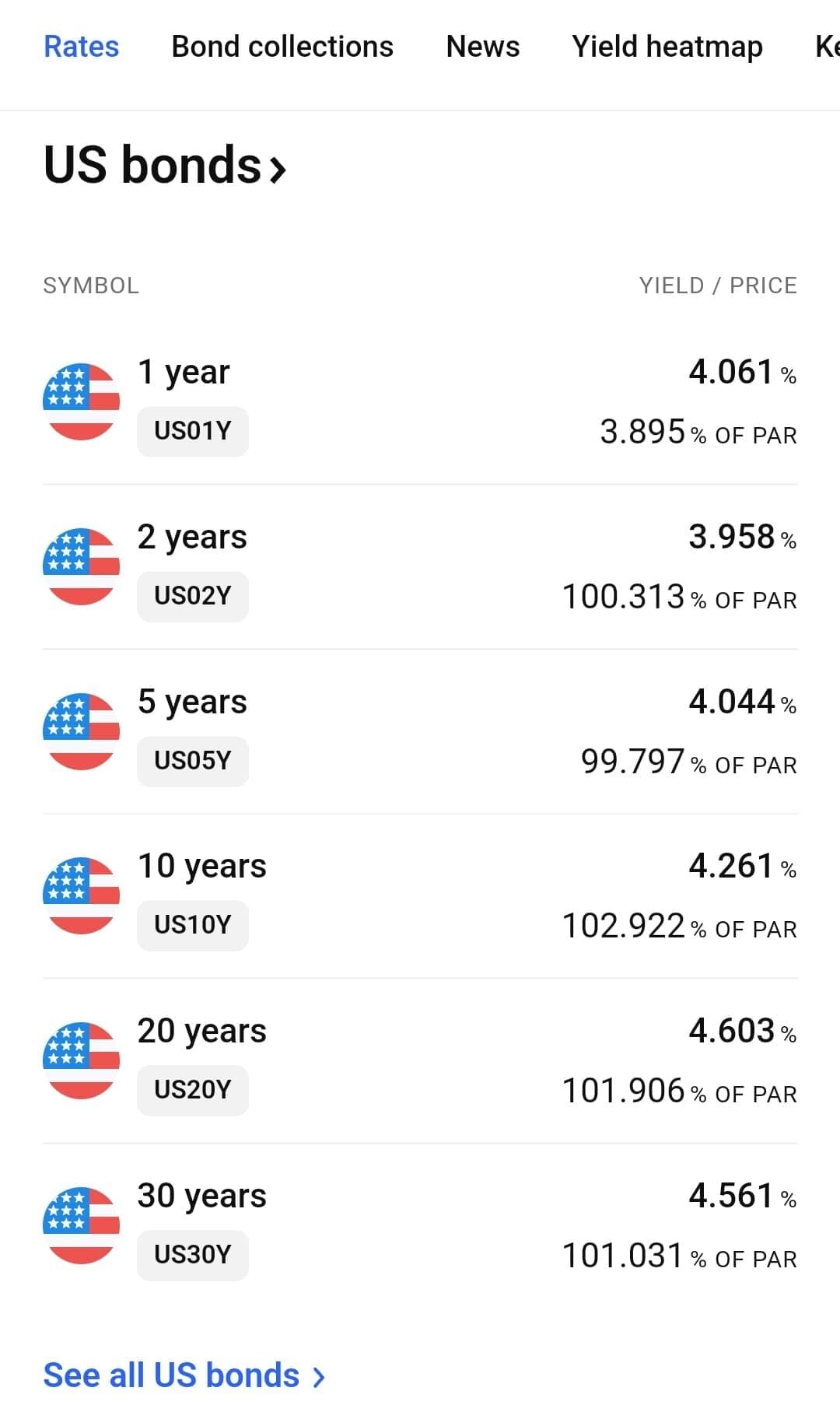

Treasury Notes (T-Notes) | 2 to 10 years | Paid semiannually | Medium-term investment with predictable income |

Treasury Bonds (T-Bonds) | 20 to 30 years | Paid semiannually | Long-term holding, retirement income planning |

- Treasury Bills (T-Bills): Short-term bonds that mature in a year or less. They don’t pay interest directly—instead, they’re sold at a discount and you earn the difference at maturity. For example, a $1,000 T-Bill might be sold for $970, and you receive $1,000 when it matures.

Treasury Notes (T-Notes): Medium-term bonds with maturities of 2 to 10 years. These pay interest every six months. Investors often use them to earn steady income while still keeping a relatively short time horizon.

Treasury Bonds (T-Bonds): Long-term investments that mature in 20 or 30 years. These pay higher interest rates due to the longer commitment. A retiree might use T-Bonds to lock in income over decades.

Municipal and State Bonds: While not federal government bonds, these are issued by local governments and sometimes offer tax advantages. For example, interest from certain municipal bonds may be exempt from federal income tax.

These bond types allow investors to balance risk, return, and investment timeframes based on their financial strategy.

What Impacts Government Bond Returns and Why

Government bond returns may seem predictable, but several key factors can cause them to fluctuate. Whether you're holding a bond to maturity or planning to sell it on the secondary market, understanding these influences is essential for maximizing returns.

Interest Rate Changes: When interest rates rise, the prices of existing bonds typically fall. For example, if you hold a 10-year bond paying 3%, but new bonds pay 4%, your bond is less attractive and may sell at a discount. This is known as interest rate risk.

Inflation: Inflation reduces the purchasing power of your interest payments. If inflation climbs to 5% while your bond only pays 2%, your real return is negative. This is why investors watch inflation data closely when buying longer-term bonds.

Credit Risk: While U.S. Treasury bonds are considered very low-risk, bonds from less stable governments (like emerging markets) carry higher risk. If there's concern the issuer may default, yields rise—but so does risk. For instance, during a debt crisis, bond yields from countries like Argentina or Greece have spiked.

Supply and Demand: If more investors rush into government bonds (often during market downturns), prices rise and yields fall. This happened during the COVID-19 crisis when many sought safety in U.S. Treasuries, pushing yields to historic lows.

These factors help explain why government bond investing still requires careful planning and timing.

How to Buy U.S. Government Bonds

Buying U.S. government bonds is straightforward and accessible to most investors.

One of the easiest ways is through TreasuryDirect, a government-run website where you can purchase bonds directly from the U.S. Treasury without paying any fees.

For example, you could log into TreasuryDirect and buy a 2-year Treasury Note or a 30-year bond with just a few clicks. The site also allows you to schedule recurring purchases or reinvest interest.

Alternatively, you can buy U.S. government bonds through a brokerage account like Fidelity, Vanguard, or Charles Schwab. This is a good option if you want to hold them alongside stocks, mutual funds, or ETFs in one portfolio.

Another method is buying bond ETFs or mutual funds, which offer exposure to many bonds at once—ideal for diversification.

Popular Government Bond ETFs

Government bond ETFs are funds that invest in a basket of U.S. or international government bonds and trade like stocks on major exchanges.

These ETFs are great for investors who want diversification, liquidity, and lower minimum investment requirements.

ETF Name | Ticker | Focus | Ideal For |

|---|---|---|---|

iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF | TLT | Long-term U.S. Treasuries | Hedging equity risk, interest rate bets |

Vanguard Short-Term Treasury ETF | VGSH | Short-term U.S. Treasuries | Conservative income, minimal rate sensitivity |

SPDR Portfolio Long Term Treasury ETF | SPTL | Broad long-term U.S. Treasuries | Long horizon investors seeking bond exposure |

iShares International Treasury Bond ETF | IGOV | Non-U.S. government bonds | International diversification, currency exposure |

iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF (TLT): Tracks long-term U.S. Treasury bonds. It’s commonly used by investors who want to bet on falling interest rates or hedge against market volatility.

Vanguard Short-Term Treasury ETF (VGSH): Focuses on bonds with maturities of 1–3 years, offering lower risk and less sensitivity to interest rate changes—ideal for conservative portfolios.

SPDR Portfolio Long Term Treasury ETF (SPTL): Provides broad exposure to long-duration Treasury bonds, useful in deflationary or recessionary environments.

International Government Bond ETFs: Funds like iShares International Treasury Bond ETF (IGOV) offer exposure to non-U.S. government debt, which can diversify geographic risk but also adds currency risk.

FAQ

Government bonds are issued by national governments and are generally lower risk. Corporate bonds are issued by companies and usually offer higher yields due to increased risk.

Yes, especially if you sell the bond before maturity during rising interest rates or inflationary periods. However, holding to maturity typically guarantees your full principal back.

Interest from U.S. Treasury bonds is exempt from state and local taxes but is subject to federal income tax. Municipal bonds may be fully or partially tax-free.

Bond prices fluctuate based on interest rate movements, inflation expectations, and investor demand. They can trade above or below their face value.

Yes, you can hold U.S. Treasury bonds or bond ETFs in IRAs or 401(k)s. They're often used to reduce portfolio risk in retirement planning.

Some bonds, like Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS), are designed to offset inflation. Traditional bonds can lose value during inflationary periods.

Savings bonds like Series I or EE are low-risk investments sold by the U.S. Treasury. They’re designed for individuals, offer tax advantages, and can't be traded on the secondary market.

Most U.S. government bonds pay interest semiannually. Some, like T-Bills, do not pay periodic interest but are sold at a discount.

Yes, international investors often buy U.S. Treasuries as a safe asset. The U.S. government auctions them to both domestic and global buyers.

TreasuryDirect allows purchases as low as $100. Bond ETFs typically require only enough to buy one share, making them accessible to most investors.

Yes, long-term bonds are more sensitive to interest rate changes and inflation. While they offer higher yields, they carry more price volatility.